In this book, Jaynes theorizes that ancient consciousness was

radically different from modern consciousness. He suggests that

ancient human beings had no sense of an interior, directing self.

Rather, they accepted commands from what appeared to them to be

an externalized agency, which they obeyed blindly, without question.

This externalized self was a consequence of the split between

the two halves of the brain. Jaynes suggests that the left and

right brains were not integrated—"unicameral"—they

way they are today. Rather, the ancient brain was "bicameral,"

with the two brains working essentially independently of each

other. The left half of the brain, the logical, language-using

half, generated ideas and commands, which the right brain then

obeyed. These commands were subjectively perceived by the right

brain as coming from "outside"—as if a god was speaking.

Jaynes adduces evidence for this astonishing hypothesis from several

sources. One is the "voices" heard by schizophrenic

patients, which Jaynes interprets as a throwback to the bicameral

mind of ancient times. Another is evidence from neurosurgery,

where patients hear "voices" upon having their brains

electrically stimulated. Another is the polytheistic gods of ancient

civilizations, which spoke directly and intimately to individuals:

"Who then were these gods who pushed men about like robots

and sang epics through their lips? They were voices whose speech

and directions could be as distinctly heard by the Iliadic heroes

as voices are heard by certain epileptic and schizophrenic patients...The

gods were organizations of the central nervous system"(73-4).

Jaynes suggests that each person had his own individual "god",

which always told them what to do. The theory further accounts

for why the gods were so naturalistic and anthropomorphic, rather

than supernatural and otherworldly.

Where did the gods go, then? Jaynes proposes that a series of

unprecedented environmental stresses in the second millennium

B.C. forced the two halves of the brain to merge into unicamerality.

(This was a cultural, rather than a biological, transformation,

Jaynes notes.) The stresses might have included natural disasters

(the story of the Flood comes to mind), population growth, forced

migrations, warfare, trade, and the development of writing. A

common denominator among all these is the introduction of complexity

and difference, things the bicameral mind deals with only with

difficulty. Jaynes suggests, among other things, that traders

in contact with other cultures might have been forced to develop

a "protosubjective consciousness" to cope with the gods

of unfamiliar people.

Jaynes suggests that the unprecedented stresses of the 2nd millennium

B.C. forced the individual into isolation, within which a sense

of I-ness appeared to fill the void left by the inadequacy of

the god. This hypothesis posits a relatively homogeneous and stress-free

existence prior to the development of consciousness. In short,

Jaynes must posit that there really was an Eden, from which humanity

Fell.

To establish the gods' disappearance, Jaynes cites a number of

illustrations and cuneiform tablets dating from Sumerian times.

He shows a stone-carven image of the King of Assyria kneeling

in supplication before an empty throne, from which his god is

conspicuously absent. The accompanying cuneiform script reads,

"One who has no god, as he walks along the street,/ Headache

envelopes him like a garment." Another tablet reads,

My god has forsaken me and disappeared,

My goddess has failed me and keeps at a distance.

The good angel who walked beside me has departed.

Jaynes interprets this as evidence of a new subjectivity in Mesopotamia.

The bicameral mind has begun to collapse into the modern unicameral

mind of the self-willed, self-aware "I", and as a consequence

the gods no longer speak to people, as they did in the days of

old (223).

These lamentations sound remarkably like the nam-shubs

mentioned in Snow Crash.

The nam-shubs also mourn something precious, and speak of confusion

and loss. It is not at all hard to guess that the loss of bicameral

tranquility may have been accompanied by unprecedented linguistic

disruption (irrespective of any causal relationship between the

two.) The Tower of Babel story—which

the nam-shubs strongly resemble—may have happened at a

time when bicamerality was breaking down.

Be this historical truth or not (and the thesis has not been widely

accepted), Jaynes has fashioned a brilliant myth of human origins.

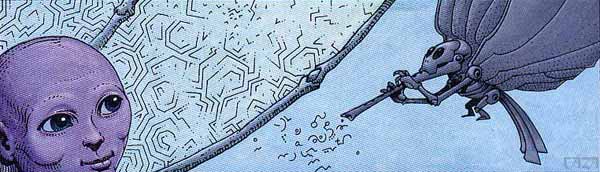

Like the authors of Snow Crash

and Macroscope,

Jaynes reaches far back into the past for an authentic story of

a Fall from wholeness. And like them, he reaches specifically

for Mesopotamian myth.